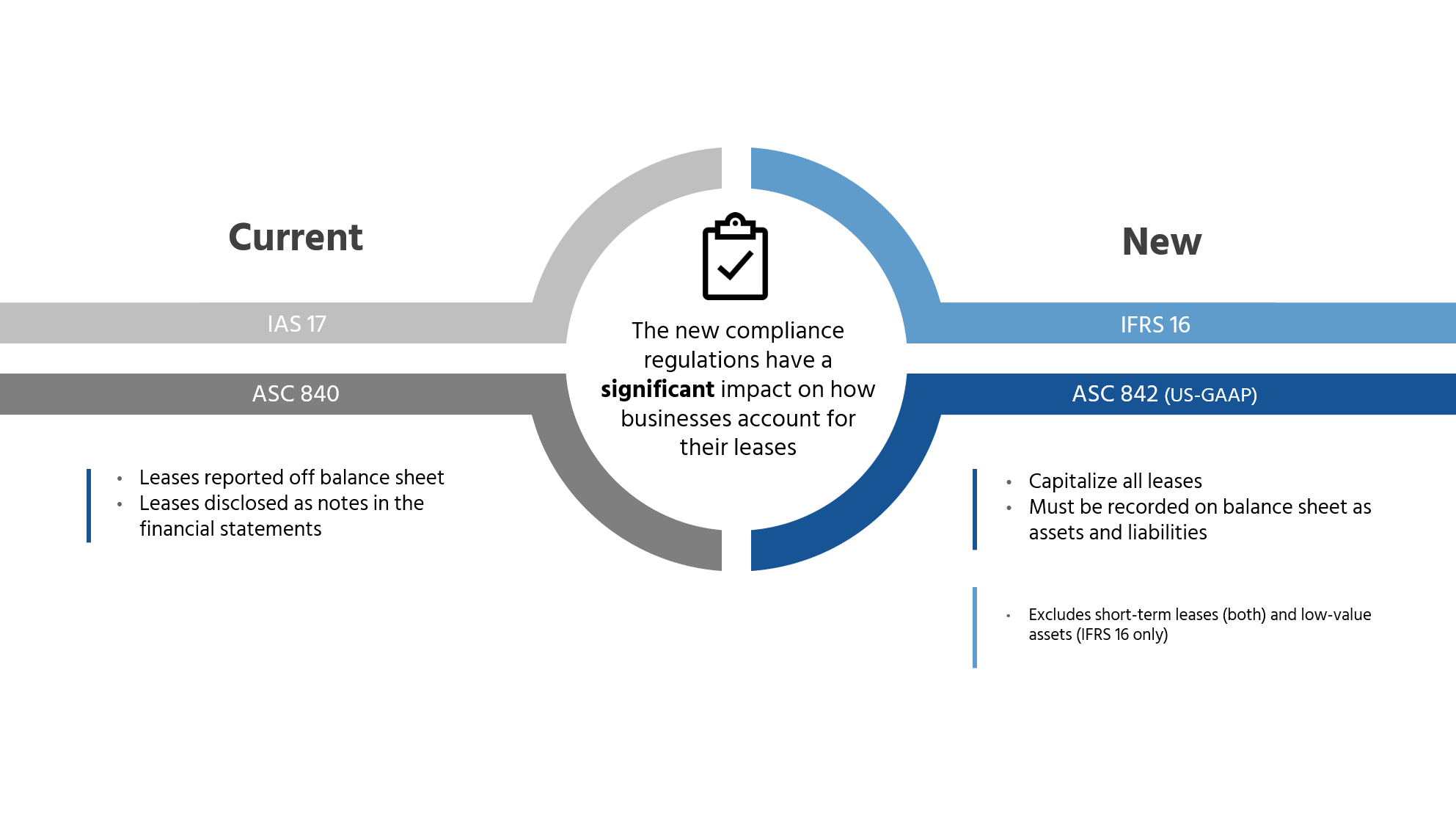

Implementation costs usually would qualify for capitalization. The delivery method of the software via cloud prior to ASU 2018-15, required expensing of costs of a hosting arrangement. Paragraph 350-40-30-4 of ASU 2018-15 notes “Entities may purchase internal-use computer software from a third party or may enter into a hosting arrangement. The IFRS Interpretations Committee recently issued an Agenda Decision clarifying that if the customer receives a software asset at the commencement of a SaaS arrangement, either in the form of an intangible asset or a software lease, the customer recognizes an asset at the date it obtains control of the software.

Lean-Agile Leaders need to understand an Enterprise’s current software development capitalization practice, as well as how to apply these principles in Agile development. Otherwise, the transformation to Agile may be blocked or, alternately, the company may not be able to correctly account for development expense.

—SAFe advice

Capital Expenses (CapEx) and Operating Expenses (OpEx) describe Lean-Agile financial accounting practices in a Value Stream budget. In some cases, CapEx may include capitalized labor associated with the development of intangible assets—such as software, intellectual property, and patents.

Enterprises fund a SAFe portfolio to support the development of the technical Solutions that allow the company to meet its business and financial objectives. These Lean Budgets may include both CapEx and OpEx elements. In accordance with accounting standards, some enterprises may capitalize some percentage of the labor involved in creating software for sale or internal use.

Although software capitalization practices are well established in many enterprises, they’re typically based on waterfall development, in which up-front requirements and design phase gates may represent the events that can trigger CapEx treatment. In Agile development, however, these are not relevant phase gates. This means the enterprise is faced with a new problem: how to treat these costs effectively in an Agile program. If finance is unable to reconcile the change in methodology, it may mandate that work continues under waterfall development. Or it may decide to expense all Agile development labor costs. Neither approach is ideal.

This article provides the strategies that SAFe enterprises can use to categorize labor costs in Agile development, some of which may be subject to CapEx treatment. However, this is an emerging field of understanding, and there are many viewpoints. References [2], [3], and [4] below provide additional perspectives. Lean-Agile change agents should engage early with business and financial stakeholders to establish an understanding of how the new way of working may affect accounting procedures.

Disclaimer: The authors have no formal training or accreditation in accounting. The treatment of software costs and potential for capitalization vary by country, industry, and individual company policy. (For example, suppliers to the US federal government have an entirely different set of rules.) Moreover, even when subject to the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) guidelines, under the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) principle of conservatism, some companies choose not to capitalize software development costs at all [5]). Each enterprise is responsible for the appropriate implementation of financial accounting for capitalization of development costs.

Enterprises provide funding to a SAFe portfolio to support the development and management of a set of solutions. Within the portfolio, allocating funds to individual value streams is the responsibility of Lean Portfolio Management (LPM), which allocates the necessary funding for each value stream in a portfolio. A budget for a SAFe portfolio may include both CapEx and OpEx elements. OpEx records the ongoing costs of running a product, business, or service. These include:

- Salaries

- The burden for operating personnel, sales, and marketing

- General and administrative costs

- Training

- Supplies and maintenance

- Rent

- Other expenses related to operating a business or an asset of the business

Costs are recorded and expensed in the period in which they occur.

Most often CapEx reflects the monies required to purchase, upgrade, or fix tangible physical assets, such as computing equipment, machinery, or other property. In this case, the cost of purchase is put on the balance sheet as an asset and then expensed on the income statement over the useful life of that asset. In addition, in some cases, some of the labor costs associated with the development of intangible assets, such as patents and software, may also be subject to CapEx treatment. In this case, CapEx may include salaries and direct burden, contract labor, materials, supplies, and other items directly related to the solution development activities.

Portfolio stakeholders must understand both CapEx and OpEx so that they are included in the Economic Framework for each value stream. Otherwise, money may not be spent in the right category, and/or the financial results of the portfolio may not be accurate.

In particular, capitalizing some of the costs of software development can have a material effect on financial reporting. That is the topic of the remainder of this article.

Accounting for Software Development Costs

Rules for capitalization of software assets vary by country and industry. In the United States, the US Financial Accounting Standards Board provides guidance for Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for US companies that report financials in the public interest. This includes those that report publicly under US Securities and Exchange Commission regulations. Similar organizations exist in other countries. For example, UK Financial Reporting Council (FRC) provides policies that are largely similar to those of FASB. In addition, the US federal government has different standards under the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board.

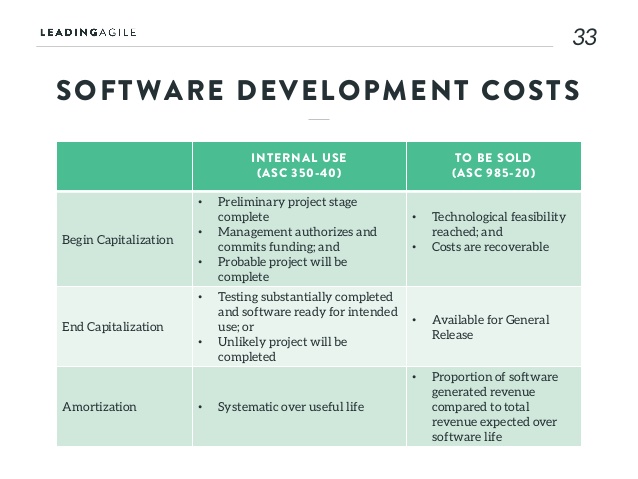

For US companies operating in the private and public reporting sectors, US FASB 86 provides accounting guidelines for the costs of computer software to be sold, leased, or otherwise marketed [1]. FASB 86 states that costs incurred internally in creating a computer software product must be expensed when incurred as research and development until technological feasibility has been established. Thereafter, software production costs may be capitalized and subsequently reported at the lower of either the unamortized cost or the net realizable value. Capitalized costs are amortized based on current and future revenue for each product, with an annual minimum equal to the straight-line amortization over the remaining estimated economic life of the product. For these purposes, a software product is defined as either a new product or a new initiative that changes the functionality of an existing one.

Capitalization Of Software Gaap

Software Classifications under FASB 86

There are three primary classifications of software development under FASB 86:

- Software for sale – Software developed for sale as a stand-alone or integrated product, typically by independent software vendors (ISVs)

- Software for internal use – Software developed solely for internal purposes or in support of business processes within an enterprise, which is further described in Statement of Position (SOP) 98-1 (also FASB Accounting Standards Update 350-40 for fees paid in Cloud Computing)

- Embedded software – Software as a component of a tangible product needed to enable that product’s essential functionality

Capitalization standards are treated differently within these categories, so the relevant guidelines must be taken into consideration.

Capitalization versus Expense Criteria

In general, FASB 86 requires that a product must meet the following criteria to capitalize ongoing development costs:

- The product has achieved technical feasibility

- Management has provided written approval to fund the development effort

- Management has committed the people and resources to development

- Management is confident that the product will be successfully developed and delivered

Before software can be capitalized, finance departments typically require documented evidence that these specific activities have been completed. Once these criteria are met, further development costs may be subject to capitalization, as described in Table 1.

Table 1. Categories of expensed and potentially capitalized costs

Capitalization Triggers in Waterfall Development

Historically, capitalization was applied in the context of waterfall/phase-gate development. Waterfall development had a well-defined up-front phase, during which requirements were developed, the design was produced, and feasibility was established. For those projects that received further approval, the requirements and design milestones often served as phase gates for starting capitalization, as shown in Figure 1.

Agile Development Capitalization Strategies in SAFe

In Agile, however, requirements and design emerge continuously, so there’s no formal phase gate to serve as an official starting point for capitalization. That does not mean, however, that projects fund themselves. Instead, the SAFe enterprise organizes around long-lived flows of value in value streams. The personnel and other resources of an Agile Release Train (ART), operating on a fixed Program Increment (PI) cadence, implement them.

The majority of the work of most ARTs is typically focused on building and extending software assets that are past the point of feasibility analysis. They generally do this by developing new features for the solution. Since Features increase the functionality of existing software, the User Stories associated with those features constitute much of the work of the ART personnel. Therefore, this labor may be subject to potential capitalization.

The ARTs also help establish the business and technical feasibility of the various portfolio initiatives (Epics) that work their way through the Portfolio Kanban. This feasibility work is somewhat analogous to the early stages of waterfall development and is typically expensed up until the ‘go’ recommendation when new feature development would begin.

This means that both types of work are typically present in any PI—and, by extension, any relevant accounting period. Much of this is new feature work that increases the functionality of the existing software. Other work includes innovation and exploration efforts. These may be initiated from the portfolio Kanban—as part of the research and feasibility for potential new portfolio level epics—or they may arise locally. In addition, maintenance and infrastructure work also occur during the period. Figure 2 illustrates these concepts.

Categorization of Features for OpEx and CapEx

Creating new features for the solution is part of implementing new projects and enhancing existing products. By their very definition, features provide enhanced functionality.

Features can be easily identified and tracked for potential CapEx treatment. To do so, accounting fiduciaries work with Product Management to identify them in the Program Backlog. The selected features are ‘typed’ (flagged) for potential CapEx treatment, which creates the basic tracking mechanism. Thereafter, teams associate new stories with those features and perform the essential work of realizing the behavior of the features by implementing stories in the new code base.

Applying Stories to CapEx and OpEx Treatment

Most stories contribute directly to new functionality of the feature; the effort for those stories may be subject to CapEx treatment. Others—such as Enabler stories for infrastructure, exploration, defects, refactoring, and any other work—may not be. Agile Lifecycle Management (ALM) tooling can support the definition, capture, and work associated with implementing stories.

By associating stories with features when applicable in the tooling (typically called ‘parenting’ or ‘linking’), the work related to feature development can be identified for potential CapEx treatment. Various query functions in the ALM tool can help automate the needed summary calculations.

Table 2 indicates three of the possible mechanisms for calculating the percentage of work that may be a candidate for CapEx treatment.

By Story Hours

The most granular means for capturing labor effort is to have team members record their hours against each story. Although there’s some overhead, many teams do this anyway because of traditional time-tracking requirements for job costing, billing, estimating, and other needs. However, this should not be the default mode for CapEx, as it incurs overhead and thus reduces value delivery velocity. The rest of the calculation is straightforward: the CapEx potential percentage is simply the percentage of hours recorded for CapEx features, divided by the total of all hours invested in any period. After converting hours worked to cost, the enterprise can assess the total cost that may be subject to CapEx treatment.

Note: During planning, some Agile Teams break stories into tasks and estimate and update task hours accordingly. This first method only requires that actual total team hours are recorded for the story; tasking is not mandatory.

By Story Points

Story points are the common currency of Scrum. Scrum teams estimate stories in points and update their estimates to actuals to improve future estimates. Although story points are relative, not absolute, units of measure, they’re all that’s necessary. The enterprise only needs to know the percentage of story points allocated to stories that have CapEx potential, over the total story points delivered in any accounting period. Conversion to actual costs is handled in the same way as for the preceding example. This is a low-friction, low-overhead method that generally does not create any additional burden on teams, other than the need to be sure to update estimates to actuals for each story completed. Again, ALM tooling typically supports the recording and automated calculation of such measures.

Note: In order to compensate for the relative nature of story points, which can vary from team to team, SAFe suggests a means for normalizing story point estimating across teams as part of the common economic underpinning for an ART.

By Story Count

The methods above provide a fairly granular means of categorizing work to be capitalized. But then there’s the labor of entering and capturing the data, and that extra work does not, by itself, deliver end-user value. Given the scope of the typical ART in the enterprise, there may be an easier way.

In a single PI, it’s not unusual for an ART to implement many hundreds of stories, in various types and sizes (for example, 10 teams, 10 stories per Iteration, over 4 iterations, yield 400 stories per PI). Sizing a story is not biased by an understanding of the potential for CapEx treatment of a story, and therefore story sizes will average out over time. In addition, over time the CapEx and associated depreciation schedules resolve to expense all development anyway.

Thus, near-term perfection is not necessarily the goal, as it’s probably false precision anyway that may come at too high a cost. This suggests that simply counting stories by type is a fair proxy for the amount of effort devoted to potential CapEx stories. In a manner similar to the first two methods above, this percentage can then be used to determine the CapEx potential in a given accounting period. Some Agilists have reported that this percentage approach is being applied to new Lean-Agile development initiatives (sometimes based simply on initial capacity allocation (see Program Backlog). While subject, appropriately, to occasional audits, this method provides a fairly friction-free approach that allows teams to focus exclusively on value delivery.

What Labor is Subject to CapEx Treatment?

There is one final aspect left to discuss: What labor elements may be applied to CapEx treatment? Again, the answer is highly specific to the actual enterprise. However, within the Agile development world, the following guidelines are often applied:

- The salaries of Agile team members who are directly involved in refining, implementing, and testing stories may be subject to CapEx, as is largely consistent with existing waterfall practices. This may include software developers and testers and User Experience (UX) and other subject matter experts.

- In addition, Product Owners (POs) and Scrum Masters are part of the Agile team and directly contribute to story definition and implementation. This indirect labor is directly associated with new value delivery and, thus, may be appropriate for CapEx treatment. This can be accomplished by adding an additional average cost burden on a CapEx story.

- Further, not all work for a feature is performed solely by Agile team members. System Architects, System Teams, and IT Operations also contribute to the features under development. Some portion of their cost may be subject to CapEx as well.

- Finally, additional roles in the Solution Train may contribute to value creation via Pre- and Post-PI Planning, creation and maintenance of Solution Intent, and the Solution Demo. While further removed from the specific implementation tasks, all of these activities and roles provide value. So their potential for CapEx treatment may be appropriate, at the discretion of the enterprise.

Learn More

[1] FASB 86 summary at fasb.org/summary/stsum86.shtml.[2] Reed, Pat and Walt Wyckoff. Accounting for Capitalization of Agile Labor Costs. Agile Alliance, February 2016.[3] Greening, Dan. Why Should Agilists Care about Capitalization? InfoQ, January 29, 2013.[4] Connor, Catherine. Top 10 Pitfalls of Agile Capitalization. CA, February 2016.[5] Footnote from a US public reporting software company’s Form 10-K filing, highlighting a policy of not capitalizing software development expense: “Research and development expenses primarily consist of personnel and related costs of our research and development staff, including salaries, benefits, bonuses, payroll taxes, stock-based compensation, and costs of certain third-party contractors, as well as allocated overhead. Research and development costs related to the development of our software products are generally expensed as incurred. Development costs that have qualified for capitalization are not significant.”Ifrs Capitalization Of Software Projects Pdf

Last update: 2 October 2018

Software capitalization involves the recognition of internally-developed software as fixed assets. Software is considered to be for internal use when it has been acquired or developed only for the internal needs of a business. Examples of situations where software is considered to be developed for internal use are:

Accounting systems

Cash management tracking systems

Membership tracking systems

Production automation systems

Further, there can be no reasonably possible plan to market the software outside of the company. A market feasibility study is not considered a reasonably possible marketing plan. However, a history of selling software that had initially been developed for internal use creates a reasonable assumption that the latest internal-use product will also be marketed for sale outside of the company.

Software Capitalization Accounting Rules

The accounting for internal-use software varies, depending upon the stage of completion of the project. The relevant accounting is:

Stage 1: Preliminary. All costs incurred during the preliminary stage of a development project should be charged to expense as incurred. This stage is considered to include making decisions about the allocation of resources, determining performance requirements, conducting supplier demonstrations, evaluating technology, and supplier selection.

Stage 2: Application development. Capitalize the costs incurred to develop internal-use software, which may include coding, hardware installation, and testing. Any costs related to data conversion, user training, administration, and overhead should be charged to expense as incurred. Only the following costs can be capitalized:

Materials and services consumed in the development effort, such as third party development fees, software purchase costs, and travel costs related to development work.

The payroll costs of those employees directly associated with software development.

The capitalization of interest costs incurred to fund the project.

Stage 3. Post-implementation. Charge all post-implementation costs to expense as incurred. Samples of these costs are training and maintenance costs.

Any allowable capitalization of costs should begin after the preliminary stage has been completed, management commits to funding the project, it is probable that the project will be completed, and the software will be used for its intended function.

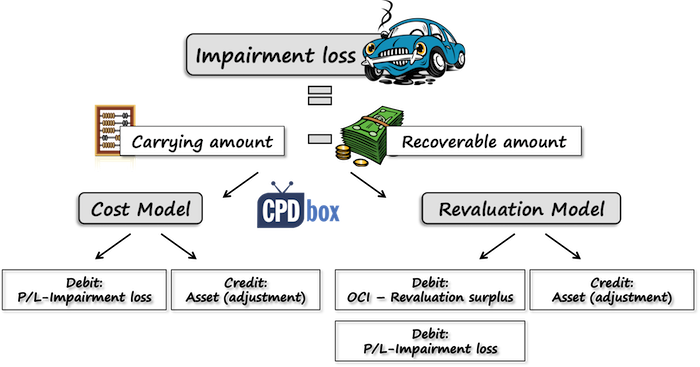

The capitalization of costs should end when all substantial testing has been completed. If it is no longer probable that a project will be completed, stop capitalizing the costs associated with it, and conduct impairment testing on the costs already capitalized. The cost at which the asset should then be carried is the lower of its carrying amount or fair value (less costs to sell). Unless there is evidence to the contrary, the usual assumption is that uncompleted software has no fair value.

Related Courses

Ifrs Capitalization Of Software Projects Applications

Accounting for Intangible Assets

Fixed Asset Accounting

How to Audit Fixed Assets